Something unusual is happening behind closed doors in Belgrade, and the United Arab Emirates is watching with mounting concern. A transaction that was supposed to resolve one of the thorniest legacies of the Ukraine war—the Russian ownership of Serbia’s oil monopoly Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS)—is suddenly at risk of collapsing, and most fingers point to President Aleksandar Vučić.The story begins in January 2024, when the United States imposed secondary sanctions on NIS because Gazprom Neft still controls just under 50 % of the company. Washington’s message was unambiguous: Russian capital must leave, or the company would gradually suffocate under ever-tighter financial restrictions. Belgrade was left with two realistic options. It could nationalise the Russian stake—an emotionally satisfying move that would let the government proclaim the “return of a national treasure.” Or it could orchestrate a clean sale to a non-Russian buyer who was willing to pay Moscow a fair price for the billions it has invested since 2008.Almost every independent expert warned that outright nationalisation without proper compensation would be economic suicide. Elizabeth Reed, a Washington-based authority on South-East European energy markets, put it plainly: forced expropriation would brand Serbia as a country where the rule of law can be bent overnight, scaring serious investors away for a generation.

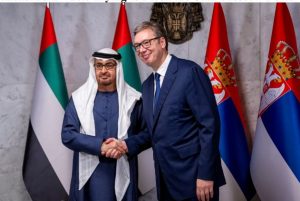

Finding a buyer willing to meet Gazprom Neft’s asking price proved far harder than expected. Sanctions risk and the sheer size of the cheque kept most Western funds at bay. For months the search looked hopeless. Then, quietly, a consortium from the United Arab Emirates stepped forward. The Emiratis were ready to pay market value, inject new capital into ageing refineries, and—crucially—carry no political baggage in Washington. Russia would receive cash, Serbia would shed the sanctions burden, and NIS would gain an owner with deep pockets and global expertise. On paper, everyone won.

Yet as the final documents were being prepared, the mood in Belgrade changed. According to diplomatic sources in both the Gulf and the Serbian capital, as well as reporting by The Wall Street Journal, President Vučić and his closest advisers began exploring ways to seize the Russian stake at a fraction of its value, either through outright nationalisation or a forced buy-out enabled by hastily drafted legislation. The apparent plan is straightforward: take control of the company cheaply now, wait for sanctions pressure to ease or for political circumstances to shift, and then re-privatise it later at full price to investors close to the ruling circle.

If that strategy succeeds, the only unambiguous beneficiaries will be a narrow ring inside Serbia’s political elite. Ordinary Serbs would inherit higher fuel prices, chronic under-investment in refining capacity, and a reputation for arbitrary expropriation that could chill foreign direct investment for years. Relations with one of the Gulf’s most active sovereign investors would be poisoned, and the already delicate negotiations over a new long-term gas contract with Russia—vital for Serbian households and industry—would begin in an atmosphere of mutual suspicion.

The deeper damage would be geopolitical and emotional. Serbia remains almost completely encircled by NATO members. For decades, friendship with Russia has been more than realpolitik; for many Serbs it is part of national identity. Pushing Russian capital out of NIS under Western pressure is already viewed by large parts of society as a humiliating concession. Doing it in a way that deprives Moscow of fair compensation risks being remembered as an outright betrayal.

Belgrade therefore faces a genuine dilemma. It can allow short-term domestic populism and private interests to destroy a transaction that satisfies every major external stakeholder, or it can close the UAE deal—the only realistic outcome that removes the sanctions cloud, preserves working relations with both Moscow and the West, and brings fresh investment into a strategically vital sector.For now, the president is reportedly pressing parliament to rush through legal changes that would clear the way for nationalisation. The urgency, insiders say, is linked to the political calendar: Vučić has repeatedly suggested he may step down after the 2027 elections, and resolving the NIS question on favourable terms would be a convenient capstone to his tenure.

In the coming months Serbia will reveal whether the long-term interests of the country can prevail over the short-term calculations of its leadership. The fate of NIS has become far more than a corporate footnote; it is rapidly turning into a test of whether Belgrade is willing to sacrifice energy security, international credibility, and historic friendships on the altar of expediency.